Lumen Autumn 2025 - Flipbook - Page 18

Music

Another oscillation of the pendulum, and I am four years old,

standing outside Bonython Hall next door. Adults swirl around

me in flapping black gowns as I cling tightly to my father’s leg.

He takes me and my little brother upstairs to the balcony, so that

we can watch something incomprehensible happen to our mother

on the stage. Some months earlier, she had danced out of the

medical school back to our car on Frome Road – I’ve passed! I’ve

passed! – and the builders on the scaffold renovating the façade had

broken into a round of applause. The medical school was not very

hospitable to young mothers in those days, and it was an enormous

achievement that she had pulled this off. Now – a single click of

that metronome – I am wearing one of these flapping gowns

myself, reading out the names of our latest crop of graduates from

that same stage. As I gaze across this sea of shining faces, I can

almost see the bewildered expressions of two small children at the

front of the balcony. They are a long way away, but they are also

very close.

“MUSIC IS AN ART WRITTEN

ON TIME: THE BEAT, THE BAR,

THE PHRASE.”

Time is supposed to be linear, but more and more it seems to

move in loops. And sometimes it stands still, just for a moment.

During the pandemic, when we had to teach piano over Zoom, one

of my students in China lost her sense of time. Her scales became

erratic; her Beethoven stalled, before scrambling towards the end

of the phrase. Finally, I asked her to place a metronome in front of

the camera, and then watched, fascinated, as it traced its trajectory

through the air and froze mid-stroke. It was the world that had lost

sense of time, not my student. In music, a fermata is a pause of

unspecified duration, represented ironically by the symbol known

as corona. After a few moments, her metronome clicked back to life

and swooped towards the next beat.

Sometimes I think time is the most profound subject of art:

Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu; Messiaen’s Quatuor

pour la fin du temps. Sometimes I think it is the only subject.

My grandfather passed away last year, but there is a plaque on a

seat in Elder Hall, acknowledging a donation he and my beloved

grandmother made during our most recent fundraising campaign.

He doesn’t really need a plaque; he is there anyway. For years I

used his metronome for my practice, until it became so wayward

I surrendered, and uploaded an App to my phone instead.

When I returned to the Elder Conservatorium after many

years of living away, the common room still smelt the same, and

the intercom in the green room made the same startling sound,

jolting performers onto the stage as if from a dream. Thirty years

after I entered this building as an undergraduate, I addressed

our new student cohort for the first time as director. I cannot

remember much about that day, but I vividly remember that other

day, 30 years earlier: the maroon t-shirt and khaki shorts I was

wearing; the Body Shop lotion I had rubbed into my legs; the vistas

of adulthood lying reassuringly ahead, where I liked them.

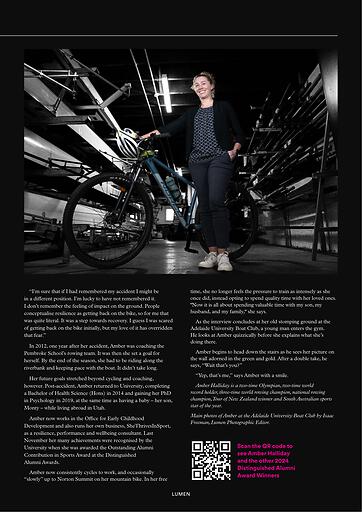

Professor Anna Goldsworthy is Director of the Elder Conservatorium

of Music, and an award-winning pianist, author and playwright.

The metronome in the image belonged to Anna’s grandfather, Reuben

Goldsworthy, also an accomplished teacher and pianist who gifted this

symbol of time to his granddaughter, along with his lifelong passion

for music.

Photos by Isaac Freeman, photographic editor of Lumen.

18