Azaghvana E-Book 2003 - Flipbook - Page 77

PART TWO

KEY SOURCES TOWARDS A SHARED SUBREGIONAL PAST

Introduction

In Part Two we will attempt to construct a pre-colonial and colonial background scenario to

explain how the Dghweɗe might be historically connected to a shared subregional past. This

part is divided into two chapters, in the context of which the second chapter becomes

increasingly historical as a result of the source situation.

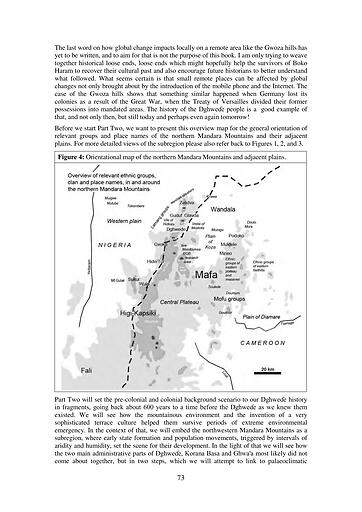

We start with the pre-colonial Wandala, and the contemporaneity between them and the DGB

(diy geɗ biy) sites on the northern slopes of the Oupay massif (see Figures 2 and 4). The DGB

sites are the most important archaeological sites with radiocarbon dates, and their distance

from Kirawa, the capital of the early Wandala state, is no more than around 25 kilometres.

The Gwoza hills are geographically sandwiched between, and are connected with, the Tur

heights and the Oupay massif to the immediate south. This makes the northwestern Mandara

Mountains specific, and suggests a possible shared past with the DGB complex, not only with

the Gwoza hills but also with Kirawa and the surrounding foothills and plains. We have

therefore defined the whole area as our investigative subregion. The Dghweɗe form part of

that subregion and we document them here in great ethnographic detail so that future

historiographical research will be able to constructively include them. We will see below that

Dghweɗe oral historical traditions include the Wandala in their original traditions, and that

they share legendary tales about a conflict over the ritual power concerning rain. In addition

to this they have a collective memory of former tributary relationships with the Wandala,

which are most likely rooted in late pre-colonial times. There are significant similarities in

terms of aspects of material culture and archaeological key finds from the DGB sites which

provide evidence for a link between early terrace cultivation and stone architecture, and we

will explore this further in the context of our Dghweɗe oral history retold throughout Part

Three.

Our second chapter describes changes not only in subregional terms, but also in the overall

political and administrative situation which occurred during the colonial period, which were

very unsettling times for the Dghweɗe. Regarding key sources, we begin with Moisel's

cartographical material from the early German period, and describe how the circumstantial

effects of the First World War brought about essential change, which eventually led the

Dghweɗe to come under British mandate rule. At that time Kirawa as a centre of Wandala

power had long gone, even though the northern part of Dghweɗe, with Ghwa'a at its centre,

still saw itself under Wandala rule. We describe the arrest of Hamman Yaji, and how the

Dghweɗe remember that they had initiated his arrest by sending a delegation to Maiduguri

after they realised that the Wandala could not protect them. We later demonstrate how

Dghweɗe increasingly lost its standing as an independent montagnard group, to the newly

developing Muslim elite in Gwoza town. We already mentioned the killing of lawan Buba in

the context of the enforced resettlement scheme of the 1950s. At the end of this chapter we

describe the circumstances of the two Plebiscites on the road to independence, in which the

Gwoza hills finally became part of modern Nigeria.

We very much hope that by connecting all kinds of sources going back about 600 years,

which relate to written, archaeological, palaeoclimatic and material cultures, an appropriate

background will be set to our Dghweɗe oral history retold. We will use some of the oral data

in Part Two, such as legends which claim to represent early pre-colonial and oral memories

concerning late pre-colonial times and the colonial history period. In the context of this, the

oral data we will use to underpin our colonial archival records are in a way the tail end of our

Dghweɗe oral history, while the bulk of our ethnographic data will relate to the pre-colonial

75